A Riff on Article 31 of UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People) … and some stories about the repatriation of Indigenous Belongings

July 19, 2024

In physics researchers have identified the existence of observer influence wherein the mere presence of someone observing a person or thing or event will have an influence on how that phenomenon behaves. The principle can be applied to sociological and anthropological studies as well. It is difficult to know precisely what one is observing because the observer’s presence influences what is happening and creates a natural distortion.

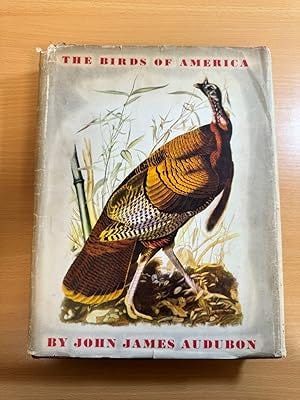

At extremes in some situations the observer and the method of study can have a detrimental impact on the subjects being observed. For example, the famous ornithologist John James Audubon was known to kill the birds he drew and to then pose the dead bodies in “natural’ positions. In fact, it was common in the nineteenth century for scientists, in the quest for knowledge, to contribute to the extinction of the very thing they were studying. In hindsight it seems obvious that as white explorers ventured outside of Europe they simultaneously acted with enthusiastic curiosity while being blithely ignorant of the devastations they were causing in their wake. There was very limited knowledge exhibited by white explorers regarding the fragility of nature or the finite nature of things found in our environment.

Culturally, as Europeans spread out across the world they were fascinated by the existence of different cultures and sought to learn more about them. They did so however with a perceptual bias that these cultures were somehow inferior and were thus bound for extinction. By extension, since these cultures were destined for extinction, it seemed fair to confiscate artifacts, totems and regalia without consideration regarding how those actions would impact the local culture or society. In some instances, the explorers saw fit to dig up graves and take human remains to be studied without any regard to the trauma caused and local customs that were violated.

In general, it did not matter to the newcomers that taking sacred objects from people would potentially bring harm to those people. The prevalent belief was that these were primitive societies that had to give way to modern Christian ways. So, like Audubon’s killing of his subjects in order to study them, collectively the European explorers who came to North America (and to other places across the globe) showed no concern that their actions were killing the very subjects they were enthralled with.

In particular those actions included stealing artifacts from indigenous populations and placing them in museums back home. These thefts were not questioned nor considered theft. As “exploration” morphed into colonization, with violence and warring encounters, consideration of local norms or laws were deemed irrelevant. While the damage caused by the confiscation of things from indigenous people can never be remedied, we are seeing today a movement to have many objects returned with apologies to the people who rightfully owned those objects.

The return of taken items is certainly a necessary element of reconciliation. It is also complex. For some communities the returned items might be used to establish their own museums to study their history in order to understand what was lost. However, because the thefts were so widespread, many communities may not have the capacity to take back and preserve all the things stolen without significant archival investment and assistance. In other cases, there may be uncertainty as to how an object was acquired, from whom and under what circumstances.

The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. has thousands of items that were obtained from various groups across North America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The Museum is actively seeking to repatriate those items including returning hundreds of items to the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation in Alberta. It is believed that at least 500 pieces in the museum’s collection came from Alberta, collected on behalf of the institute. Some of these were paid for (albeit for a fraction of their real value), others were simply taken. Regardless, the museum now recognizes the need to return these items to their rightful owners no matter how they were acquired.[1]

The return of artifacts and other objects to indigenous groups is part of the action required to live up to the intent of Article 31 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), which enshrines the right of Indigenous Peoples to control their cultural heritage.

In September 2023, after nearly a century had past since it was stolen and placed in a Scottish museum, a totem pole was formally welcomed home in a rematriation ceremony to Nisga'a territory. Colonial ethnographer Marius Barbeau took the pole without the consent of the House of Ni'isjoohl — one of around 50 houses within the Nisga'a Nation — during a period when the Nisga'a Peoples were away from their villages for the annual hunting, fishing and harvesting season.

The Ni'isjoohl memorial pole is a house pole that was carved and erected in the 1860s. It tells the story of Ts'wawit, a warrior who was next in line to be chief before he was killed in a conflict with a neighbouring nation. Noxs Ts'aawit (Dr. Amy Parent), a member of the nation and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous education and governance, first discovered the memorial pole was in Scotland four years ago. She said her ancestral grandmother had the pole carved in the 1860s and erected in honour of Ts'wawit.

"We know that a carver breathes life into a pole when it is first carved. And so, after that point we consider that totem pole to have a living spirit in it and to be a relative. And so, it's like bringing a family member home after being gone for almost 100 years," she said.[2]

Earlier in 2022 a 200-year-old Susk'uz headdress that had been on display at the Royal Ontario Museum for about 140 years was returned to its rightful owners. The Keyohwhudachun (chief) headdress is a cultural artifact of the Maiyoo Keyoh, a family territory about 100 kilometres northwest of Prince George, BC.

Jim Munroe, president and CEO of the Maiyoo Keyoh Society, says the headdress is significant for several reasons, including the fact that it is tied to the Indigenous family territory system of land management and governance.

"It's something that is not only significant to us, but I think it allows an opportunity for general society to make a connection to the first nations society that sustained us for hundreds, if not thousands, of years."[3]

Munroe happened to spot the headdress while browsing through the Royal Ontario Museum's online collection in 2017. He says it was taken by a Catholic priest, Father Adrien Morice, in about 1887 at a time when the early Canadian government forbade First Nations from engaging in any traditional ceremonies.

There is a saying that ‘’you can never step in the same river twice’’. The past has irreparably shaped the present and returning taken items cannot undo the harm caused. Regardless, it remains an important step for indigenous people to have an opportunity to reconnect with their ancestors and restore aspects of their culture that were thought to have been lost.

Returning items allows indigenous people to recapture their own history and culture. It ensures that the interpretation of the significance of these historical items is conducted through their eyes. In this way we can all learn more accurately from them.

While there is no practical way to eliminate the observer effect, nor can we fully mitigate against perceptual biases, we can all learn to respect other cultures and to try to contain any influence we may have on them. There is a quote that has been attributed to Walt Whitman, the American poet: “Be curious, not judgmental.” Before we assess, interpret or judge another culture through our own cultural lens, we need to simply be curious and allow the people we are interested in learning more about, tell their own story.

We ought to learn a lesson from Audubon’s efforts. Among Audubon’s depictions of 489 species in his prodigious folio The Birds of America, a concerning number of the species have since gone extinct or are currently classified as critically endangered. In retrospect it makes no sense that to draw them accurately in a natural setting he saw it acceptable to kill them. We know enough today to do better.

1946 Edition.

NOTE: If you are interested, The Royal BC Museum and the Haida Gwaii Museum publishes the Indigenous Repatriation Handbook. It is available as a online book to support communities and museums in the repatriation of belongings.

https://www.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/indigenous/repatriation-handbook

You can find this Handbook at this link.

[1] https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/alexis-nakota-repatriation-smithsonian-1.5344488

[2] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/memorial-totem-pole-returned-1.6981891

[3] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/susk-uz-headdress-maiyoo-keyoh-royal-ontario-museum-1.6672972

Please share this post or this publication with anyone in your network who might enjoy these readings.

Share this article:

Share this publication and find all our previous articles: