Image Source: https://www.saugeenojibwaynation.ca/node/75

In previous articles we have raised concerns that the litigation of indigenous land claims perpetuates distrust between the government and indigenous people. This assertion is based on the premise that the government often relies on old arguments that have already been turned down by the courts and are therefore not valid. The government needs to accept these decisions and the liability for improper conduct which in the past failed to maintain the honour of the Crown [1]. In particular the Government must also accept its fiduciary responsibilities[2] to the indigenous people who reside in Canada. Arguments to the contrary are inconsistent with the government’s stated policies and contribute to the continuation of strained relations.

It has to be recognized that the courts do serve a valuable function and remain as necessary participants in the resolution of land claims and other grievances against the Crown or more specifically against the Canadian government and in some instances the provinces. It has been the courts’ role in the past to clarify legal rights AND help define the government’s fiduciary responsibilities and what it means to uphold the “honour of the Crown”.

An important practical consideration is how claims can be resolved when other interests, particularly the private ownership of land, are involved. In negotiations with government many indigenous groups have adopted the politically safe position of asserting they have no interest in disrupting private ownership interests in disputed lands. However, as with any legal position or boundary it is not an absolute. In other words, it is not true that privately held land is or ought to be immune from indigenous claims. If those privately held lands are part of a dispute because they were acquired through some malfeasance or some other type of breach of a treaty or of law, then it seems reasonable that the courts weigh in to determine an equitable remedy for the damages caused by such breaches.

A recent case was decided on December 9, 2024 by the Ontario Court of Appeal involving a land claim by Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation that highlights the importance of exercising some caution when considering the boundaries of what is and isn’t at play when it comes to indigenous land claims.

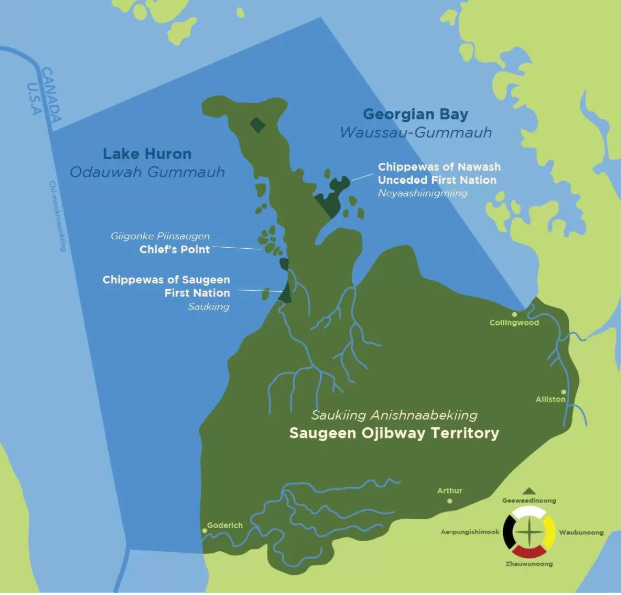

The Saugeen are an Ojibwe people who were covered by Treaty No. 72 under which they surrendered all of their territory, which included 500,000 acres on the Bruce Peninsula, except for two reserves. The Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation (otherwise known as the Saugeen Ojibwe Nation or SON) has initiated a couple of claims alleging the Crown breached its fiduciary responsibility and failed to uphold the honour of the Crown with respect to parts of the Bruce Peninsula (also referred to as the Saugeen Peninsula) and with respect to the of waters (or parts thereof) of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

The Ontario Superior Court[3] ruled against SON with respect to the claim for the “waters” denying the claim based on a lack of evidence about exclusive and sufficient use at the time that the British Crown asserted sovereignty in 1763. Moreover, it is generally held that no one can assert title over waterways as they must remain unencumbered in order to be accessible for navigation. The Ontario Court of Appeals however decided on August 30, 2024 that the matter should be remitted back to the trial judge to consider: “whether Aboriginal title can be established to a more limited and defined area.” The appeals court found that the trial judge had not erred in her application of the test for proof of Aboriginal title to the claim area[4] but that the plaintiffs (the SON) ought to be permitted to seek a declaration of title to a subset of the claim area.

The trial judge’s assertion that, at common law, navigable water is not capable of ownership and is subject to a public right of navigation, while correct, is not absolute. The Court of Appeal’s decision effectively upholds or stands for the notion that Aboriginal title could exist to land submerged by navigable waters where title to submerged lands may have no practicable effect on the public right of navigation and may be entirely compatible with it. In order to determine if this is the case the matter was sent back to the trial judge in order to work out the extent of the claim more precisely.

The other SON claim concerns the disputed ownership of a stretch of beach at the north end of the Saugeen's Indian Reserve 29 (IR 29), referred to as Chi-Gmiinh or Sauble Beach (the “Disputed Beach”), and whether the parties intended for the disputed section of beach to form part of IR 29 under Treaty 72. The disputed section of beach was originally excluded from the Saugeen's reserve by the Provincial Land Surveyor at the time the boundaries of the reserve were marked. The Imperial Crown[5] later issued Crown patents for the lots along the Disputed Beach, which eventually came into the possession of the Town of South Bruce Peninsula (the Town) and certain private landowners.

The SON brought an action against the governments of Canada and Ontario, the Town of South Bruce Peninsula, and the private landowners seeking various declarations including that the disputed lands are part of their reserve lands. The claim further alleges that the Crown breached its fiduciary duty and acted in a manner inconsistent with the honour of the Crown by failing to ensure the surveyor included the disputed lands as part of the reserve and, therefore, within the exclusive possession of the SON.

The trial judge applied principles of historic treaty interpretation and found that the common intention of the parties under the Treaty was to include the Disputed Beach as part of IR 29. The trial judge held that the Crown acted in a manner contrary to the honour of the Crown and breached its fiduciary duties to the Saugeen by not ensuring that the reserve lands were properly surveyed and failed to protect and preserve the Saugeen's reserve entitlement. Therefore, SON’s interest in its unceded reserve lands was not extinguished by the Crown patents.

In response to the SON's claim for the return of the disputed section of beach, the private landowners advanced the defence of bona fide purchasers for value, but the Trial Decision held (agreed with SON) that this defense did not apply since the private landowners had inherited their lands. The Trial Decision concluded that the principle of reconciliation rendered the strict application of this defense inequitable. In other words,the application of the bona fide purchaser defense would defeat or nullify the Saugeen's constitutionally-protected interests in and spiritual connection to the Disputed Beach. Therefore, the conclusion was the SON claim takes precedent in order for the outcome to be fair and equitable in the balance of interests.

The Ontario Court of Appeals[6] upheld the trial judge’s decision in this case and noted: "[t]here is no principled reason that a treaty-protected reserve interest of a First Nation should, in every case, give way to the property interest of a private purchaser, even an innocent, good faith purchaser for valuable consideration." This reflects the sui generis nature of the relationship between the Crown and indigenous people. As a result, the doctrinal rules of property right, including upholding the rights of bona fide purchasers may not be absolute. Rather the courts must weigh the rights associated with the assertion of Aboriginal title with the legitimate rights of private landowners in order to establish a conscionable and equitable remedy.

This is an important case and establishes the fact that any legal recourse must consider the impact on all interested parties and ensure that the result is just and equitable. It effectively establishes the correct notion that collectively Canadians have to accept that the goal of reconciling disputes with indigenous groups may supercede our own private interests in the pursuit of fair outcomes.

[1] In referring to the honour of the Crown we mean acting in ways that uphold the integrity of the Crown/government and hold the government to a standard of good faith to protect the interests of indigenous people.

[2] A fiduciary is held to take actions in the interests of the people it represents and to not act in self-serving ways even if the actions taken are contrary to its own interests.

[3] Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation v Canada (Attorney General), 2023 ONCA 565

[4] The claim included “submerged lands” under the waters of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

[5] The term “Imperial Crown” used here refers to the U.K. rule whereas we use the term the “Crown” to refer to the government of Canada.

[6] Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation v. South Bruce Peninsula (Town), 2024 ONCA 884

We were forced to relocate we never gave up our land rights. What in the justified infringement are you saying.