As Canadians continue on our collective journey towards understanding the experiences of indigenous peoples, we must remember that one of the most important parts of that journey is embracing the truth, no matter how difficult it is at times to face. We also need to recognize that in understanding Indigenous cultures we need to acknowledge the vast diversity represented by the many different people who have populated this land since time immemorial. With that diversity comes an immense tapestry of beautiful practices and traditions. While there is value in looking at the common history and practices, it is more important to consider and respect the distinct traditions and experiences of individual groups too.

Understanding the existing diversity found amongst the Canadian Indigenous people requires accepting that there is complexity. For example, the Indian Act, first introduced in 1876 and amended from time to time, applied only with respect to people with ‘’Indian status’[1]’ and did not reference other indigenous people such as the Metis, Inuit or non-status Indians. While the apparent intent of the Act was to provide for the administration of the relationship between the government and the First Nations, the underlying motive of the Act was to eradicate First Nations culture and force assimilation into the Euro-Canadian society of the colonists.

An 1895 amendment to the Indian Act prohibited the celebration of “any Indian festival, dance or other ceremony.” Powwows, the Sun Dance and the Ghost Dance were all banned under this amendment[2]. Another amendment in 1914 outlawed dancing off-reserve, and in 1925, dancing was outlawed entirely. The Sun Dance is a sacred ritual practiced by Plains Indians in the U.S. and Canada and amongst some peoples in the Rocky Mountain region.[3] It is a ritual of regeneration, healing and self-sacrifice for the good of one’s family and tribe.

The Sun Dance ceremony is practiced at the summer solstice, the time of longest daylight and can last for four to eight days. The Sun Dance is a ceremony of dances and songs passed down from and to the next generations. It includes playing the traditional drum and prayer with the ceremonial pipe, and fasting from food and water before some of the dances. In some cases, it can be a grueling ordeal that includes a spiritual and physical test of pain and sacrifice. In the past the ritual involved the piercing rawhide thongs through the skin and flesh of a dancer’s chest with wooden or bone skewers. The thongs are tied to the skewers then connected to the central pole of the lodge. The Sun Dancers dance around the pole leaning back to allow the thongs to pull their pierced flesh. The dancers do this for hours until the skewered flesh finally rips. The Sun Dance is a rite of passage to manhood. It is a sacred as a bat mitzvah or bar mitzvah might be to a Jewish family or a christening to a Catholic.

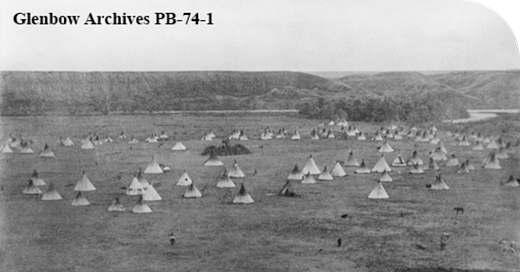

The dance is practiced differently by each tribe, but basic similarities are shared by most rituals. In some instances, the Sun Dance was a private experience involving just one or a few individuals. But many tribes adopted larger rituals that involved the whole tribes or sometimes many tribes gathered to celebrate the Sun Dance together. Lodges or open frames built of trees, rawhide or brush are prepared with a central pole at the center.

Despite the ban in Canada many tribes continued the ritual in various forms. It was one aspect of the Indian Act that was not strictly enforced. The period immediately following the Second World War involved much societal introspection in Canada, and led to a reconsideration of some of the more restrictive and oppressive measures imposed by the Indian Act. The process of reform included, for the first time, consultation with First Nations communities about changes to the Indian Act. This lead to a new and revised Indian Act that was given royal assent on 20th June 1951. The resulting overhaul removed some of the most offensive political, cultural and religious restrictions including the banning of dancing and in particular the Sun Dance ceremony.

It is important to understand that the Sun Dance is not something that should be viewed as a quaint nostalgic ceremony but rather to appreciate that for some communities it is an extremely sacred and private rite[4]. In 1993, US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota nations held "the Lakota Summit V" in response to what they believed was a frequent desecration of the Sun Dance and other Lakota sacred ceremonies. The international gathering of about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes unanimously passed a 'Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality' prohibiting non-natives from participating in the ceremonies and prohibiting exploitation, abuse, and misrepresentation of their sacred ceremonies.

In 2003, the 19th-Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe of the Lakota asked non-Indigenous people to stop attending the Sun Dance (Wi-wayang-wa-c'i-pi in Lakota). He stated that all can pray in support, but that only Indigenous people should approach the altars. This statement was supported by keepers of sacred bundles and traditional spiritual leaders from the Cheyenne, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota nations, who issued a proclamation that non-Indigenous people would be banned from sacred altars and the Seven Sacred Rites, including and especially the Sun Dance, effective March 9, 2003 onward.

As part of our path and reconciliation we must first accept the wrong that was perpetuated on indigenous people when the white newcomers enforced laws on them aimed at eliminating their culture. In correcting these wrongs non-indigenous people need to accept that cultural elements are sacred to each group in ways that are unique and special to each people. Decisions regarding how rituals and ceremonies are to be practiced are for the given people to decide and for the rest of us to respect.

The whole notion of assimilation was purposefully designed to eliminate indigenous culture. It follows that any hint of cultural appropriation or attempts to attenuate the nature of sacred ceremonies resurrects feelings of oppression amongst indigenous people. Non-indigenous people should be and are becoming more aware of indigenous cultures and what makes them unique and distinct. It is part of adopting diversity as a core value that defines Canadians. Accepting indigenous cultural diversity is a means of defining the Canadian identity for the future.