Image source and credit: Alberta's provincial flag. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld) (Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Reconciliation between Canada and its Indigenous population is marked increasingly through words — spoken in land acknowledgements and written as names on things. A solid majority of Canadians accept that injustice to Indigenous people in Canada amounts to genocide, and many of us feel shame and remorse but few think they have personal responsibility, or how to exercise responsibility even for injustices continuing today.

The "Dish With One Spoon" is a treaty between the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples and Britian and so therefore Canada, signifying an agreement to share and protect common territory, especially in what is now southern Ontario. It acknowledges that all who share the land, including newcomers, are invited to participate in this treaty of peace, friendship, and respect. This Treaty, visualized as a wampum belt, emphasizes sustainable and equitable sharing of resources. The Dish With One Spoon is a reminder of the ongoing responsibility to care for the land and each other and is often used in contemporary land acknowledgments. It also embodies the teachings of taking only what you need, keeping the environment clean, and leaving something for the future generations.

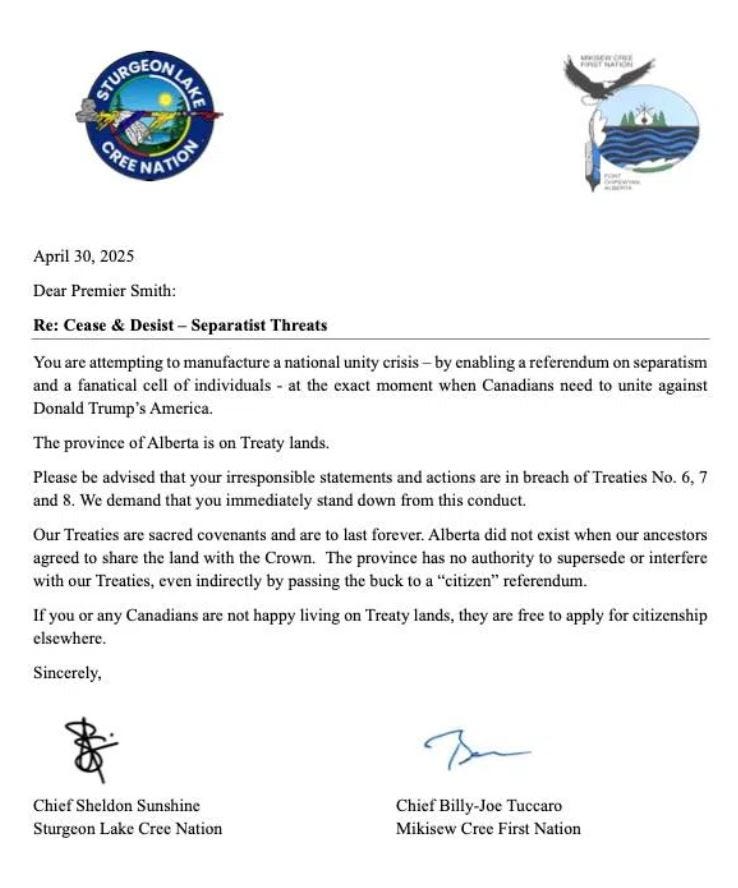

In a recent exchange on LinkedIn some participants lauded the efforts of indigenous leaders in Alberta who weighed in on rising sentiments with respect to provincial separatists’ goals and stated categorically that the province does not have an independent right to determine whether or not they can separate from Canada. Rather, as the Chiefs asserted the existing Alberta area treaties are sacred documents. They were entered into before Alberta was a province and it is clear that Alberta exists on Treaty lands that is to be shared with the Crown. Disturbingly, the Albertan separatist movement comes at a time when we need unity across and within Canada to protect our mutual interests against the existential threat posed by the current administration in the U.S.

Excerpt from the recent Cease and Desist letter (see fully letter below) as sent to the Alberta Premier:

The Full Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation and Mikisew Cree First Nation’s Cease and Desist Letter to the Alberta Premier. April 30, 2025:

One separatist noted that the text of the Numbered Treaties that cover the land that is now Alberta do not mention sharing. Rather the text suggests that the land was ceded to the Crown completely and apart from land reserved by the text for exclusive use by First Nations communities, the land is for the exclusive use of the Crown. This argument unfortunately is narrow in its interpretation of those Treaties and ignores historic context as well as adopting a rigid legalistic stance that is counterproductive to Canada’s mission of reconciliation.

The historic backdrop that gets us to today’s reality is complex, nuanced and subject to interpretations with respect to which narrative we want to pursue. A strict and narrow interpretation that denies a responsibility to share the land serves to establish a rigid legal framework to deny indigenous participation in political decisions that has a profound impact on the established relationship between them and settler society. It is a big issue that deserves to be at the forefront of any discussions and one that ought to overshadow any immediate separatist efforts which are nothing more than a political reaction to the fact that the recent federal election resulted in the maintenance of the Liberals as the ruling federal party! It is decidedly undemocratic not to defer to election results and declare that if you don’t like the results you no longer want to play by the rules. It also dramatically cuts against the grain of Conservative philosophy which is anchored in the maintenance of existing institutional arrangements regardless of their immediate efficacy.

The Dish With One Spoon Treaty is but one concept that informs how we should interpret treaty relationships. Anyone who has studied the negotiations of the numbered treaties knows that the precise wording of those documents was controlled by the government negotiators and does not accurately reflect intent. Thus, a narrow interpretation perpetuates the notion that land was completely ceded to the Crown versus the understanding that was established that the intent was to share the land. Granted that this more liberal interpretation could be seen as equally biased. Notwithstanding there is plenty of evidence to support that the discussion and verbal agreements were centered on the understanding that there would be sharing1.

In prior arrangements including the Two Row Wampum, the Covenant Chain and the numerous Peace and Friendship treaties, precedents were established to secure understandings with respect to the sharing of land and resources. These prior agreements are wholly consistent with the indigenous view that the intent of the Numbered Treaties was to maintain a sharing relationship. This argument is furthered by the implicit intent of the Royal Proclamation of 1783 which clearly sets aside territory that in part encompasses what is now considered to be Western Canada as indigenous land that could only be ceded to the Crown.

Given that the Numbered Treaties are flawed in many ways including the fact that they were not written in a way that reflects the true agreement between the Crown and the signatory indigenous groups, it is fallacious to suggest that those Treaties represent the ceding of all land to the Crown. Moreover, any litigation based on the idea that those First Nations who entered into the Numbered Treaties happily and willingly gave up their rights in exchange for reserved lands merely perpetuates a system of apartheid that we must eradicate in order to fulfill Canada’s destiny to be a fully-fledged democracy that is capable of balancing a diverse set of interests.

Alberta is a land mass that was occupied by First Nations groups including Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Pikini (Peigan) and Gros Ventre. Other groups, including the Kootenay and the Crow, made expeditions into the land to hunt bison and go to war. The Tsuu T’ina, a branch of the Beaver, occupied central and northern parts of the land, while the north was also used by the Slavey. It is estimated that these people began occupation of the area as early as 5000 BCE. Prior to becoming a province, it was part of a larger parcel of land that included what is today Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. In 1870 that land, which was referred to as Rupert’s Land and was sold to Canada by Britain to help further the establishment of Canada from coast to coast to coast and to link British Columbia with the rest of the fledgling nation.

While the legitimacy of the British claim of land ownership, based on the Doctrine of Discovery, is debatable it remains that Rupert’s Land was the land considered in the Royal Proclamation and was thus governed by that Proclamation. It became necessary for the formation of the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta to seek agreements from the impacted First Nations and this lead to the negotiation of the known “Numbered Treaties” that preceded the formation of the provinces.

Once the Numbered Treaties were completed the way was paved for the enactment of legislation to create the western provinces. This included the passing of the Manitoba Act (1870), the Saskatchewan Act (1905) and the Alberta Act (1905). Initially, control over the Crown lands and resources in each province was maintained by the federal government. However, Alberta was given control over the Crown lands and resources in 1930.

Notwithstanding, Alberta is bound by the concept of “the honour of the Crown” and therefore has a fiduciary responsibility to the First Nations which means it is obliged to act in the interests of the First Nations without regard for personal or other interests. Current separatist sentiments cannot negate this obligation. Arguably the province cannot unilaterally separate without the consent of all First Nations who are signatory to Treaties that cover the land that is the province. In other words, the First Nations have a de facto veto on any such efforts.

But this is a legalistic argument that is subject to the potential flaws that inevitably arise when trying to interpret Treaties and other relevant instruments without considering the more important cultural and societal contexts. The creation of Canada was intended to unify people across a great expanse for the common good. The creation of Alberta then was an essential undertaking to create Canada. As then as is now, without Alberta there is no Canada and without Canada there is no Alberta. The future then and our future today is about discussing shared values and shared outcomes and this discussion must include the first people who occupied the shared land.

A land acknowledgement is a formal statement that recognizes the traditional territory of Indigenous peoples and their enduring relationship with the land. It's a way to honor the Indigenous history and presence on a particular land, often used at the beginning of events, on websites, or in email signatures. Land acknowledgements are becoming increasingly common as part of reconciliation efforts and to acknowledge the Indigenous current and historical presence on the land.

They can be a meaningful gesture of reconciliation, but at times they can become a "check-the-box" housekeeping item at the start of a meeting or event. The essence of a land acknowledgement is developing an understanding of the historical context, being respectful of the lands that the indigenous people have lived on it since time immemorial, and in good faith living up to intent of the Treaties that were made. It is about developing a common set of values that govern how we live together on lands and in a country that was meant to be shared.

In an era of reconciliation, land acknowledgements are political statements meant to recognize First Nations, Inuit, and Métis territory. However, as mentioned above and as many Indigenous people argue, they've grown to become superficial and performative. Further, narrow interpretations of Treaties only serve to continue problematic relationships that interfere with the positive growth of Canada through reconciliation.

Land acknowledgments can be empty gestures if they are not followed by concrete actions that support Indigenous peoples and communities. In Alberta it seems there is an urgency in the need to acknowledge that Indigenous communities must be included in all discussions regarding the future of the land and its resources.

Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013), author of Braiding Sweetgrass, shares these wise words:

The story of our relationship to the earth is written more truthfully on the land than on the page. It lasts there. The land remembers what we said and what we did. Stories are among our most potent tools for restoring the land as well as our relationship to land. We need to unearth the old stories that live in a place and begin to create new ones, for we are storymakers, not just storytellers.

We are in the midst of creating a revised, more accurate and inclusive story of Canada. Let’s be unified in seeking a common narrative that is based on the value of sharing and being masters of our own destiny.

See for example Talbot, Robert, Negotiating the Numbered Treaties: An Intellectual and Political History of Alexander Morris, UBC Press, Purich Publishing, 2019. As Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North West Territories in the 1870s, Alexander Morris was responsible for negotiating Treaties 3 to 6, and renegotiating Treaties 1 and 2. According to Talbot, both Morris and the First Nations negotiators viewed the treaties as the basis of a new, reciprocal arrangement among those who would share the land. Indeed, by the end of his appointment, Morris was seriously at odds with a myopic federal administration that favoured inaction over honouring its treaty promises.