Important Lessons on How to Interpret Treaties

October 25, 2025

In 2021, the Supreme Court of British Columbia ruled that the Province of British Columbia unjustifiably infringed the Treaty 8 rights of Blueberry River First Nation by “permitting the cumulative impacts of industrial development to meaningfully diminish Blueberry’s exercise of its treaty rights.” The case, known as Yahey v. British Columbia was the first case to consider the cumulative effects of industrialization on treaty rights and found that the “piecemeal infringement” of Aboriginal and treaty rights significantly undermines Indigenous peoples’ constitutional rights.

The Blueberry River First Nations is an Indian band based in the Peace country in northeast British Columbia. The band is headquartered on Blueberry River 205 Indian reserve located 80 kilometres northwest of Fort St. John. The band is party to Treaty 81.

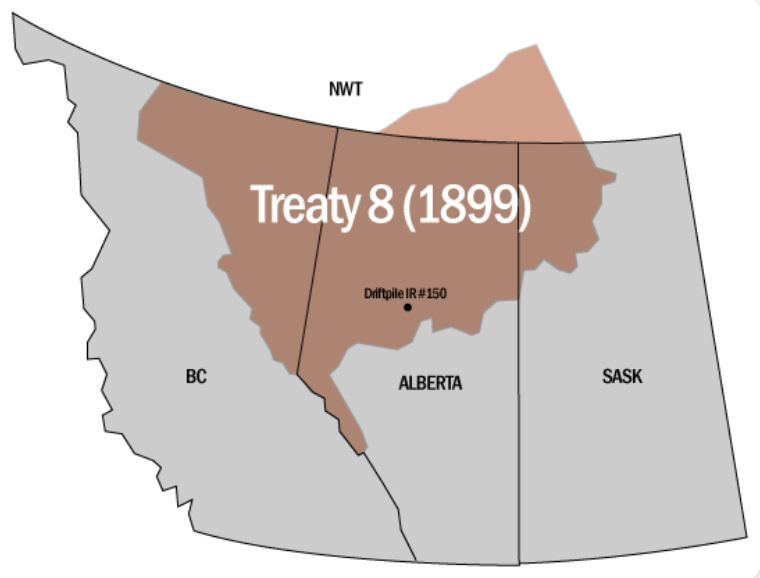

Map original source: http://www.driftpilecreenation.com

The full territory covered by Treaty 8, 840,000 sq km (320,000 sq mi) is larger than France and includes northern Alberta, northeastern British Columbia, northwestern Saskatchewan and a southernmost portion of the Northwest Territories.

After finding that Blueberry River First Nation’s rights under Treaty 8 had been infringed, the court ordered the Government of British Columbia to consult and negotiate with Blueberry to establish regulatory mechanisms to manage and address the cumulative impacts of industrial development on Blueberry’s treaty rights. A six-month timeline to reach a solution was set and the Province was prohibited from permitting further industrial activity in Blueberry’s traditional territory, absent an agreement. Implicitly the management of traditional territory and the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent should be considered as inherent Indigenous Rights as well as being a specific treaty right.

This is significant because Blueberry’s traditional territory overlies the vast natural gas and liquids resource of the geological Montney Formation in northeast British Columbia. The Montney reserves form the anchor source for most of the BC LNG industry including: LNG Canada’s $40 billion liquefied natural gas processing and export facility under construction at Kitimat, British Columbia; which will be serviced by the Coastal GasLink Pipeline; the planned Woodfibre LNG export terminal on the Howe Sound fjord near Squamish, British Columbia; and the Nisga’a Nation’s proposed Ksi Lisims floating LNG terminal on Pearse Island, British Columbia.

The Yahey case is also important as it establishes important legal principles with respect to how the courts ought to interpret treaty rights. The ruling follows principles first laid out by Justice McLachlin in the case referred to as R v Marshall, [1999] 3 SCR 456 who, in her dissent, set out nine principles of treaty interpretation that have been cited as the authoritative statement on treaty interpretation by many courts since. These principles are:

Aboriginal treaties constitute a unique type of agreement and attract special principles of interpretation.

Treaties should be liberally construed and ambiguities or doubtful expressions should be resolved in favour of the aboriginal signatories.

The goal of treaty interpretation is to choose from among the various possible interpretations of common intention the one which best reconciles the interests of both parties at the time the treaty was signed.

In searching for the common intention of the parties, the integrity and honour of the Crown is presumed.

In determining the signatories’ respective understanding and intentions, the court must be sensitive to the unique cultural and linguistic differences between the parties.

The words of the treaty must be given the sense that they would naturally have held for the parties at the time.

A technical or contractual interpretation of treaty wording should be avoided.

While construing the language generously, courts cannot alter the terms of the treaty by exceeding what “is possible on the language” or realistic.

Treaty rights of aboriginal peoples must not be interpreted in a static or rigid way. They are not frozen at the date of signature. The interpreting court must update treaty rights to provide for their modern exercise. This involves determining what modern practices are reasonably incidental to the core treaty right in its modern context.

The most central principle listed above in ascertaining the rights and obligations in a historic treaty is directing the court to “choose from among the various possible interpretations of common intention the one which best reconciles the interests of both parties at the time the treaty was signed.” In R v Marshall it was necessary for the Supreme Court of Canada to ascertain the meaning of the Mi’kmaq Treaties of 1760-1761. These treaties were signed at the conclusion of the Seven Years War (between France and England) and these Treaties were struck between the British victors and the Mi’kmaq who had allied themselves with the French. Over time the court has evolved to the understanding that it could not simply rely on the text of a treaty to understand the common intentions of the signing parties but also had to consider the proper historical context in order to uncover the true meaning and intent of a given treaty. This ultimately increases the complexity of interpretation and places the court in a significant role as a result.

While common intention can in part be gleaned from the actual text and language used in the treaty itself, doing so also requires reading that text in the context of the historical circumstances under which the agreement was made. However, we know that treaties were written in English and often omitted important points of agreement, including the understanding that the right to Aboriginal Title was maintained over traditional lands. that were clearly understood by the indigenous parties to those treaties, as a precondition to entering into the agreement. Hence the need for a set of guidelines that Justice McLachlin laid out above that compels the courts to consider several factors when determining the true common intent of any treaty.

Treaties between the Crown and First Nations are sui generis agreements meaning the parties intend to create legally binding obligations and each assumes certain specific obligations. They are given special status and protected by the Constitution under s. 35. The full effect makes the reconciliation of treaty rights and obligations a complex undertaking. The preference of many lawyers and others is to rely on the strict interpretation of the written treaty text which would certainly simplify things. However, doing so would deny Indigenous rights and ignore the common intent of the parties in entering into the treaties in the first place (hence the need for Justice McLachlin’s nine principles of interpretation)

Of course, one of the problems as illustrated in R. v. Marshall is that in order to fully understand context the interpreter often has to go back hundreds of years and attempt to ascertain the relevant facts that demonstrate what the parties actually intended. Also, given the inherent bias created by the fact that treaties were written in English the interpreter may need to rely on oral histories or on any extrinsic evidence (evidence outside of the document itself) in order to deduce actual intent.

For thousands of years, the Dane-zaa ancestors of the Blueberry River First Nation practiced a way of life intimately connected to and dependent on the land, wildlife, and natural resources of the Upper Peace River region of northeastern British Columbia. In 1899, the Crown promised to protect that way of life indefinitely or, as the Indigenous signatories to Treaty 8 understood, for “[a]s long as the sun shines.” Without this solemn promise, the Cree, Dane-zaa, and Chipewyan signatories of Treaty 8 would not have entered into the treaty and agreed to share the territory’s lands and resources.

Moreover, while a single oil or gas extraction project might have a minimal impact on the treaty rights of the Indigenous people who are party to Treaty 8, over time the amount of industrial development in the oil and gas sector has impacted a full 85% of the Blueberry’s traditional territory. The B.C. Supreme Court found that “[t]he Province has taken up lands to such an extent that there are not sufficient and appropriate lands…to allow for Blueberry’s meaningful exercise of their treaty rights.”

Understandably the nine (9) principles of interpretation and other legal doctrine adopted by the courts has made the resolution of treaty obligations and restoration of Indigenous rights a complex and difficult undertaking. In particular the principle of interpreting treaty rights in a fluid way that accounts for modern realities potentially places the courts in a role as social architect rather than that of impartial adjudicator.

The reality faced by many Indigenous groups when trying to negotiate a settlement to their claims is one of frustration precisely because the provincial and federal governments have been unable or unwilling to adopt a negotiating posture that includes the courts guiding principles for interpretation. Arguably it is incumbent upon both levels of government to reflect on those guiding principles as a necessary precondition to settlements and to ensure they are upholding the honour of the Crown.