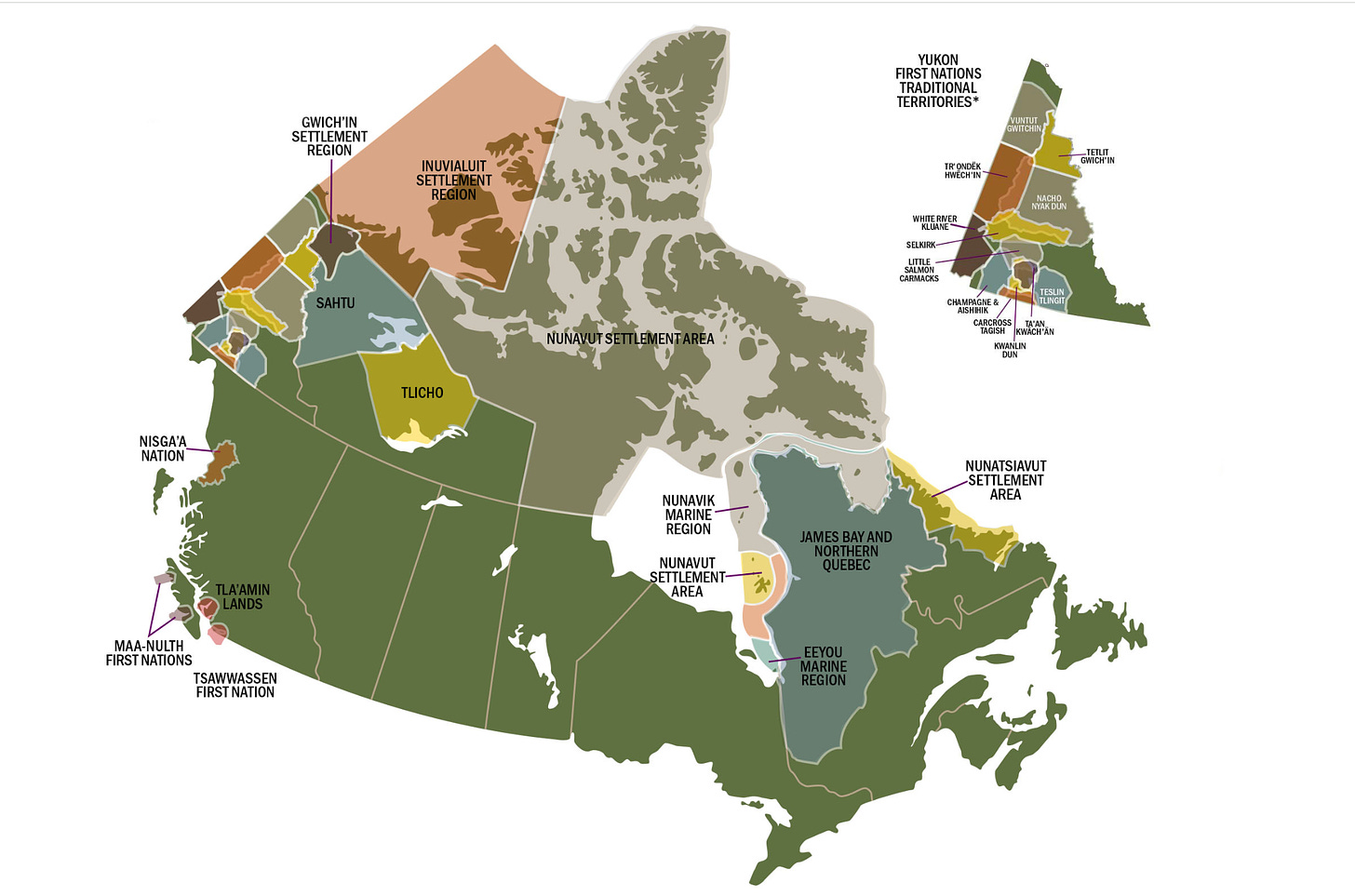

Modern Treaty Map (Source: https://landclaimscoalition.ca/ )

Indigenous Relations is one of the most significant political issues currently being dealt with in Canada and yet many Canadians are unaware of the actions that have taken place and continue to evolve in negotiations between the Canadian government (and in many cases the provincial governments) and various First Nations across the country. Perhaps the biggest and potentially most controversial set of issues is settling the numerous land claims that have arisen. Moreover, every land claim has a unique set of legal and contextual circumstances that have to be weighed and considered in order to fashion a fair and equitable outcome.

Since 1973, Canada has signed 26 Comprehensive Land Claims1, 18 of which included some provisions for self-government. In addition, the Canadian government has signed four self-government agreements during that same period. Notwithstanding, there is a lot of work yet to be done. There are approximately 100 negotiations ongoing with respect to land claims and self-government. The process is unfortunately arduous given the myriad of interests and other factors that complicate progress.

Since 1973, Canada has signed 26 Comprehensive Land Claims, 18 of which included some provisions for self-government. In addition, the Canadian government has signed four self-government agreements during that same period.

One example that is illustrative of the complexity of this type of bargaining is the Algonquin Land Claim which concerns ownership over 600,000 km2 and capital transfers in the billions of dollars. The Algonquins of Ontario (AOO) represent ten Algonquin communities in the Ottawa River watershed, including: the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation and the communities of Antoine, Bancroft, Bonnechere, Greater Golden Lake, Mattawa/North Bay, Ottawa, Shabot Obaadjiwan, Snimikobi and Whitney and Area. The AOO assert that they have Aboriginal rights and title that have never been extinguished and have continuing ownership of the Ontario portions of the Ottawa and Mattawa River watersheds and their natural resources.

An agreement in principle was reached and was ratified in 2017 but has not been fully concluded yet. This agreement helps identify the many considerations that need to be made in developing a comprehensive agreement which becomes a modern treaty between Canada and a First Nation group.

In the end the AOO will receive ownership of 117,500 acres of land and a cash payment of $300 million. The following principles form the foundation of the future settlement:

Land will not be expropriated from private owners.

No one will lose existing access to their cottages or private property.

No one will lose access to navigable waterways.

No new First Nation reserves will be created as part of the treaty.

Approximately 4% of the Crown land in the claim area is proposed for transfer.

The vast majority of the Crown land base will remain open to all existing uses.

After transfer, Algonquin lands will be subject to municipal jurisdiction, including the same land use planning and development approvals and authorities as other private lands.

Land transfers will:

restore historically significant sites to the Algonquins,

contribute to the social and cultural objectives of Algonquin communities,

provide a foundation for economic development for the region.

Algonquin harvesting rights will be subject to provincial and federal laws necessary for conservation, public health and public safety

The Algonquins will continue to develop moose harvesting plans with Ontario.

Fisheries management plans are to be developed for the Algonquin settlement area, with the first priority being protection of the sensitive fisheries of Algonquin Park.

No lands will be transferred from Algonquin Provincial Park.

Ontario will continue managing its provincial parks and conservation reserves, with the Algonquins having a greater collaborative planning role

The proposed land transfers will affect some non-operating parks in the settlement area.

A new provincial park and an addition to Hungry Lake Conservation Reserve in Frontenac County are being recommended, as well as an addition to Lake St. Peter Provincial Park.

Negotiations of land claims require considering historical contexts, legal foundations and competing rights. It is imperative that these negotiations protect the traditional ways of life of Canada’s indigenous people. Given that the objectives of these negotiations are essentially agreements between nations, it is paramount that they consider future implications which include, amongst other things, the rights of indigenous people to participate in management decisions with respect to land and resource use. Furthermore, land claims are part of a greater context and must include elements related to future self-government.

The implications for Canada are significant.

One of the underlying principles in the agreement is the recognition of the AOO, as a legitimate political entity that has the right under our Constitution to enter into an enforceable agreement with the Canadian government.

This continues the process of evolution that is changing how Canada is governed by introducing a new construct of government operating within the overall structure of the Canadian political landscape. It is a slow process but will inevitably have profound influence on the nature of Canadian culture – which is a very positive step forward.

In February of 2024 a settlement was reached with the Matsqui First Nation with respect to a claim involving a corridor of land that was removed from the Matsqui reserve in 1908 by Canada and given to the Vancouver Power Company — now B.C. Hydro — to build a tramway. The settlement recognizes that the compensation given to Matsqui at the time was inadequate, and that Canada breached an agreement to build and maintain rights of way over the rail line, resulting in Matsqui land being cut off from any kind of practical use. Under the Special Claim Policy of the federal government the Matsqui will receive compensation in the amount of $59 million.

Specific Claims deal with past wrongs against First Nations2. These claims which have been brought forward since the late 1900s are made by First Nations against the Government of Canada and relate to the administration of land and other First Nation assets and to the fulfilment of historic Treaties and other Agreements. For example, a specific claim could involve the failure to provide enough reserve land as promised in a treaty or the improper handling of First Nation money by the federal government in the past.

Specific Claims are separate and distinct from Comprehensive land Claims or modern treaties.

The distinction is important. Specific Claims deal with issues that are defined in the context of a treaty or other legal instrument. As such they are relatively narrow in scope and therefore tend to lean towards financial compensation as a resolution. Given this narrow definition it is not surprising that such settlements are seen as steps in fixing the relationship between the federal government and a given First Nation group. In the case of the Matsqui a larger land claim arising out of the loss of their treaty lands and being alienated from their traditional lands remains to be negotiated.

Understanding the difference between Specific Claims and Comprehensive Claims is just the beginning of appreciating the complexity of managing land claims and the evolution towards self-government. This work is on the path to reconciliation, and it is expected to be a long road. It is incumbent on all Canadians to learn about the issues and the underlying principles that guide us collectively to resolving the historic wrongs that have robbed our indigenous people of their culture, heritage, lands and use of their lands.

Comprehensive Claims deal with Indigenous rights based on traditional use and occupancy of lands which were never changed or extinguished by way of a Treaty.

The Specific Claims Commissions and Tribunals have been proposed since 1947 when the Indian Act was amended to reverse its ban on use of Band funds to sue the Federal Government. In 2009 a Commission was formed to speed up the settlement of these grievances, however has yet to conclude this decades long backlog of work.