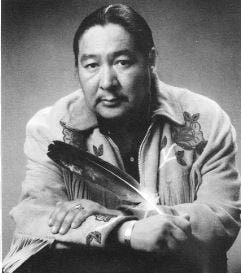

Elijah Harper: (March 3, 1949 – May 17, 2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elijah_Harper

One of the fundamental principles underlying liberal democracies is the rule of law. The rule of law however defines the source of governmental authority and unfortunately is often misinterpreted in application. In a short article we cannot do justice to the full meaning and impact of the rule of law in shaping constitutional law in Canada but we can raise a couple of important points to be contemplated with respect to how the Constitution and the rule of law work to protect the inherent rights of indigenous people.

One of the axioms of the rule of law is that laws are supreme and are to be applied to all citizens equally without exception. Notwithstanding, within Canada, indigenous people have inherent aboriginal rights that existed before there was a Canada and therefore provide them with a special status that some refer to as Citizens Plus. This is not a contradiction as some liberal thinkers might suggest. Rather it reflects another principle of the rule of law that requires that laws be created to embody the “normative order” to create a good and just society.

Within Canada normative order means many things such as the special rights provided to French Canadians to protect their language and culture in Quebec where they are the majority, and elsewhere in Canada where they form a minority. Normative order includes the principle of protection for minorities and this protection is essential to the maintenance of a working democracy. We cannot rely on a simple rule whereby a majority always prevails precisely because doing so risks seeing minority rights trampled on.

This is a difficult concept and while Canada has institutionalized the special rights of certain groups like French Canadians and Indigenous People the definition and exercise of those special rights continues to evolve out of necessity.

When it comes to aboriginal rights we must be clear that these are not rights established by the Canadian Constitution1[1]. Rather they existed long before European settlers first came to North America. We refer to these as aboriginal rights precisely because the term refers to the laws and rights that existed prior to the forming of Canada, or indeed the arrival of Europeans.

When discussing the Canadian Constitution, it is important to note that it does not create aboriginal rights but rather recognizes their prior existence. Section 35 of the Constitutional Act, which was included only after significant protests by indigenous people, was added to ensure these rights were enshrined in the Act, reads as follows:

35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) “treaty rights” includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons.

Aboriginal rights have been interpreted by decisions of the Canadian Supreme Court to include a range of cultural, social, political, and economic rights including the right to land, as well as to fish, to hunt, to practice one’s own culture, and to establish treaties.

Section 35 also recognizes that Aboriginal rights are “existing.” Notwithstanding, the Supreme Court of Canada has stated that this means that any Aboriginal rights that had been negotiated away by treaty or other legal processes prior to 1982 remained extinguished and therefore are not protected under the Constitution. Importantly while the Constitutional Act does not revive these extinguished rights, the courts have adopted the doctrine that the phrase “existing aboriginal rights” must be interpreted flexibly so as to permit the evolution of their definition over time. Essentially the court recognizes that the rights of indigenous people need to be interpreted in ways that acknowledge their special status and the duty of the government to protect them. For further clarity, the Constitution affirms aboriginal rights but does not define them. Therefore, what “aboriginal rights” includes has been heavily debated, discussed and litigated, and these rights have been defined over time through various Supreme Court cases, new modern treaties and other legal means.

The passing of the Constitution Act, 1982 and its interpretation is an evolution (as one would expect of any Constitution in a democracy). In 1990, an attempt to amend the constitution through negotiations between the provinces to recognize Quebec as a distinct society within Canada failed to be ratified largely as a result of the actions of one man who stood up in protest to defeat the accord precisely because the governments had failed to include representatives from the indigenous communities as part of those deliberations.

That man was Elijah Harper an Oji-Cree from the Red Sucker Lake First Nation in northern Manitoba who holds the distinction of being the first aboriginal elected as a Member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly. In his view, and the view of many other indigenous leaders the Meech Lake Accord promoted the narrative that Canada was created by the English and the French, ignoring the role of First Nations people in building Canada. It did nothing to protect First Nations cultures or languages.

In each of the twelve days preceding the ratification deadline established by Brian Mulroney for the Accord, the Manitoba government requested unanimous consent in the Assembly to ratify the agreement. Each day, Harper, while holding an eagle feather, voted no, denying unanimous consent, so the resolution could not be debated and voted on. This was followed by Newfoundland and Labrador cancelling its vote on the Accord.

Harper’s lone dissent defeated the Meech Lake Accord and gained him national prominence. It lead to inclusion of the indigenous inherent right to self-government as part of the Charlottetown Accords in 1992 (for clarity, both Accords where attempts to amend the Canadian Constitution). While the Charlottetown Accord also when down to defeat it remains that, in Canada, there is momentum towards enhancing and enshrining existing aboriginal rights in law through the courts, negotiations between the federal government and indigenous groups and through statutory amendments.

The evolution of indigenous/aboriginal rights is an essential ingredient in establishing the unique and enviable brand of democracy Canada has and is continuing to develop. There is a long way to go but we all owe a debt of gratitude to the legacy of Elijah Harper who stood up and made a statement that changed our country for the better by demonstrating to all Canadians and especially to other indigenous people that their voices mattered. Elijah Harper died on May 17, 2013 but he will forever be remembered for the actions he took back in 1990.

Generally, when we refer to the Canadian Constitution, we are referencing the Constitution Act 1982.